Africa’s many small and under-capitalized banks, laden with bad debt, are inflicting more pain on already embattled economies.

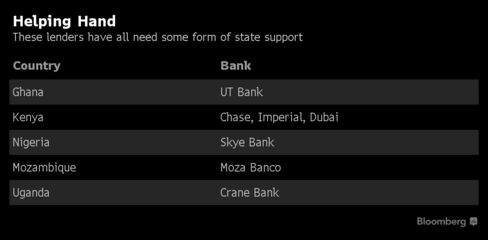

Regulators may have no choice but to force lenders to consolidate or close. A third of Nigeria’s 21 banks may be under-capitalized. Much smaller Uganda has 25 banks and last month suffered one collapse. Kenya has had three failures since August last year and with 40 lenders, boasts almost one bank per million people. Angola’s 30 or so banks may need to boost reserves by $4 billion, while a Mozambican lender was rescued by the central bank in September. Ghana is telling banks to combine and raise funds through the stock market.

“The consequences of inaction will be disastrous,” said Robert Besseling, a Johannesburg-based executive director at business risk consultancy Exx Africa. “Uncontrolled bank failures pose significant contagion risks to other banks, state-owned enterprises, and private businesses.”

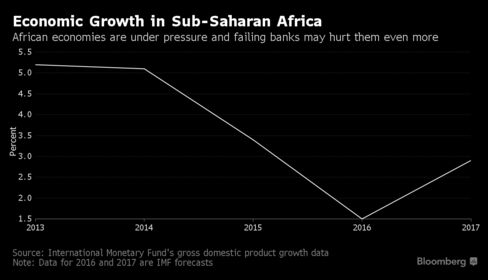

Zombie banks, a term coined by Edward J. Kane of Boston College in 1987, are typically all but insolvent save for government support. They have injured economies from Japan to Europe and now it may be Africa’s turn. The continent has been battered by falling commodity prices, an enduring drought, weakening currencies and a slowdown in China, its biggest trading partner. A plethora of lenders edging toward collapse have governments nervous and central banks scrambling to find increasingly scarce liquidity.

‘Death Spiral’

“When banks get in tough times, often initiated by an economic slowdown, they hold back capital, reinforcing the economic slowdown which bites down harder on bank performance,” said Adrian Saville, chief strategist at Citadel Investment Services in Johannesburg. “In its worst form, this takes the shape of a death spiral.”

Trying to save them may be an exercise in futility because zombie banks don’t have a reputation for regeneration, said Saville. After the Japanese bubble burst in 1990, a raft of zombie banks staggered along for the next 20 years, which hamstrung the Japanese economy, according to Saville. By contrast, he said, when U.S. banks were allowed to fail it meant the lenders that emerged from the ruins were able to behave and perform functionally.

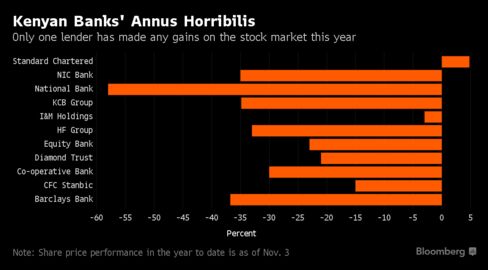

The threat of failing African banks is compounded by the fact that “there are some countries with far too many banks,” said John Ashbourne, an economist at Capital Economics Ltd. in London. “Kenya stands out as an example of this. Provided that problems continue to be centered in the region’s smaller banks, I expect regulators will intervene or force consolidation.”

“The smaller Kenyan banks are facing a potentially dangerous cocktail of declining margins, declining liquidity and deteriorating asset quality, which could at best force consolidation within the sector, or at worst precipitate a full-blown banking crisis,” Ronak Gadhia, an equity analyst at Exotix Partners LLP in London, said in a note. “The pro-activeness of the regulator is likely to be critical in determining the outcome.”

It used to be that domestic consumer banks in Africa had a captive market that foreign lenders, hungry for government work and deal fees, weren’t much interested in. That’s changed and it’s adding to the difficulties.

“For Africa’s small domestic banks the advantage of having local roots is now being eroded by mobile money apps and more sharing of credit information,” said Mark Bohlund, a London-based economist at Bloomberg Intelligence. “This should lead to increased bank consolidation through mergers and acquisitions, which, in theory, should weed out smaller less-efficient banks.”

In Mozambique, which is struggling to repay debt after the commodity slump slashed export revenue and the depreciation of its currency increased the cost of foreign loans, the central bank has imposed restrictive measures to force small banks to either recapitalize or be sold, according to Besseling. Moza Banco SA was taken over by regulators in September with a view of returning it to health and selling it.

The risk of uncontrolled bank collapses is “high” in both Mozambique and Angola, he said, adding that banking crises are also possible in Nigeria and the Democratic Republic of Congo.

Bankruptcy Beckons

“The Angolan banking sector landscape could see some changes in the not so distant future,” said Tiago Dionisio, a Lisbon-based analyst for Eaglestone Advisory SA. That overhaul will probably be driven by rising non-performing loans and more demanding regulatory changes to boost capital levels. “The current number of banks operating in the country might prove to be unsustainable.”

The demise of Uganda’s Crane Bank Ltd. and other lenders may lead to opportunities for buyers. Lenders like South Africa’s FirstRand Ltd. and Nedbank Group Ltd. want to expand and declining valuations across the continent may be the break they’ve been waiting for.

In the meantime, Africa’s banks won’t be lending as much as they could, stalling consumer spending and curbing business growth.

“Depositors are afraid of placing deposits with zombie banks, so they don’t get funding to grow their book and grow out of the zombie loans,” said Kokkie Kooyman, a portfolio manager at Cape Town-based Denker Capital. “The zombie loans on the balance sheets prevent loans for new projects that will allow the country to grow.”

While it may save some jobs at the affected banks, keeping troubled lenders alive adds no value to the economy, he said.

As for what to do with those banks, it may be best to sell them to specialized vehicles that will act like vultures, Kooyman said. “They’ll pick the bones clean and life goes on.”