Last week, the Reserve Bank of India said an 89-year-old lender, founded by the Devkaran Nanjee family of Mumbai, is unfit to conduct normal banking business, thanks to its financial position which is so precarious that it may collapse if allowed to continue.

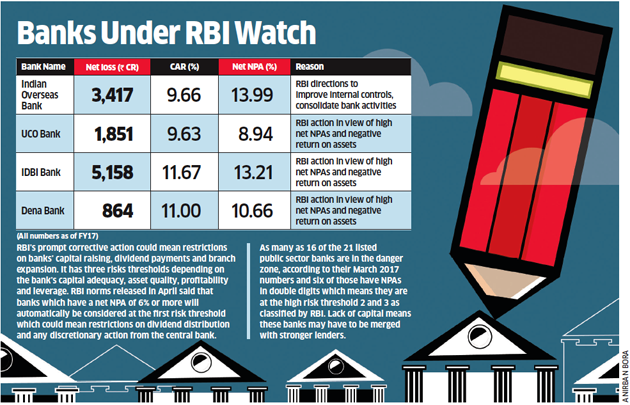

The entity, Dena Bank, was the fourth public sector lender to attract RBI’s attention. Some months back, another 90-year-old lender which thrived even during the British period, Indian Overseas Bank, was diagnosed with a similar disease. IDBI BankBSE 0.50 %, which traces its history to a special act of Parliament, is gasping for breath, and so is Kolkata-based UCO BankBSE 0.59 %.

Investors wonder whether a single shareholder—the government—can nurse all these entities back to health or throw in the towel. Is there a justification for one shareholder running so many loss-making lenders? Out of the 21 listed state-run banks, not more than four large ones have a future as rising bad loans and provisions have eroded the profitability of the rest, financial metrics provided by the regulator show.

At the end of the fourth quarter of the fiscal year ended March 2017, the collective losses for these lenders stood at Rs 10,000 crore, according to a Credit Suisse report dated May 23.

Just four banks—State Bank of India, Bank of Baroda, Punjab National Bank and Canara Bank—are financially stable. These four lenders have either increased their profit or swung back from a loss reported in the fiscal year ended March 2016.

If a weak bank is merged with a strong one, the government need not shell out capital separately. Also, many of these banks have branches in the same locality and a closure of some of these would reduce costs and help redeploy personnel in a better way.

Strong banks like State Bank of India and Bank of Baroda would be in a better position to raise capital from investors because of their strength, reducing dependence on government, unlike Dena Bank or UCO Bank.

India’s state-dominated banking that came into life with the nationalisation of banks in 1969 to help the poor is in tatters with a poor capital position. Total stressed loans of the Indian banking sector amounted to `12 lakh crore, a large part of it coming from public sector banks. These banks under the guidance of the state lent recklessly which has led to a situation where taxpayers have to bail them out.

With government disinterested in rescuing them, the call for their consolidation is gaining ground. Even if the state wants to drive some social agenda, it could be done with a few instead of a score of lenders. Reserve Bank of India’s deputy governor Viral Acharya at a FICCI event recently in Mumbai mentioned how banks need to be something citizens can ‘bank upon’.

Highlighting the need for consolidation in the sector, he said the system could be better off if banks are consolidated into fewer but healthier ones.

“Synergies in lending activity and branch locations could be identified to economise on intermediation costs, allowing sales of real estate where branches are redundant. Voluntary retirement schemes (VRS) can be offered to manage headcount and usher in a younger, digital-savvy talent pool into these banks,” he said.

WHAT AILS THEM

For banks, the raw material is capital that comes from shareholders. The government, which has to own at least 51% in lenders by statute, is not in a position to provide capital. And private capital can’t flow either because of law.

Under the government’s Indradhanush road map announced in August 2015, the government had earmarked a total of Rs 70,000-crore investment in public sector banks between fiscals 2015-16 and 2018-19.

Government had estimated that these lenders will have to raise as much as Rs 1.1 lakh crore from the markets to meet their capital requirement under Basel-III norms. That’s a drop in the ocean for these banks which, according to ratings agency Fitch, will need 80% of the $90 billion (about Rs 5.8 lakh crore) required by Indian banks in the next two years. Because of their huge bad loans, they can’t focus on expanding the business even as private lenders such as HDFC Bank and Kotak Mahindra Bank are acquiring new customers. As a result, public sector banks are losing out on vital low-cost deposits, which are fast dwindling.

These banks are not in tune with developments in technology where youngsters call for fancy products that old state-run banks are struggling to provide. As a result, retail customers are moving away from them even as they lose out on new digital-savvy customers. This is reflecting in their declining market share as well.

“How many technology innovations have been reported from the smaller public sector banks and I doubt how much of automation are they prepared for,” said Kuntal Sur, partner, financial services, PwC India.

According to a report released by Credit Suisse, all new loan growth last fiscal came from private sector banks, their market share has risen to 27% from 20% in the second quarter of 2014 and deposits’ share is at 23%, up from 18%.

WHAT FUTURE

Though state-run banks’ financials are crippled, their franchise and customer trust are not broken. With India growing at more than 7%, there are enough opportunities to do business.

There is ample opportunity in the Indian banking scene, still enough scope for growth of PSBs. The argument around size and performance also does not hold true because there are a lot of small-sized private banks which are doing a very good job like IndusInd Bank, Kotak Mahindra Bank, among others,” said TT RamMohan, faculty for finance at IIM Ahmedabad.

The branch network and the human talent still make them attractive for private buyers too. So, the government could also consider letting private banks merge with these lenders.

“I believe private banks should also be allowed to throw their hat into the ring for buying these PSBs,” says PWC’s Sur. “The aim should be to bring down their share of business in the economy.”

The government may be in no mood to loosen its purse strings and provide capital to small lenders which do not perform. It may not have shown its hand on what it intends to do with them. But the day of reckoning is closer than ever as Kotak Mahindra Bank vice-chairman Uday Kotak said.

“The time has now come to bite the bullet. The state, sooner or later, may have to make the difficult choice of putting in more good (taxpayers’) money after bad or being open to ‘strategic’ choices. I wonder whether that can happen now or sometime after 2019,” Kotak said in his annual letter to shareholders.