Soon after becoming finance minister in 2014, Arun Jaitley, in an interaction with bankers, asked what is the one thing that he could do to make their lives better.

There was near unanimity in the answer: Give us a bankruptcy law.

But the bankers’ reluctance to use the law in the past 18 months since the Lok Sabha put its stamp of approval on the Insolvency and Bankruptcy Code, reflects how few realised what was in store.

The government had to come up with two ordinances — an emergency legislation before Parliament votes on it — in less than 24 months since the promulgation of the law to ensure it is used.

That the banking lobby group wrote to the Reserve Bank of India seeking a restructuring package nine months after the law was passed, reflected the industry’s hesitation to use the law it was waiting for years. Not a single bank took a big defaulter to be tried under the bankruptcy law till the Reserve Bank of India chose the dirty dozen in June.

Doing that would have created massive holes in banks’ books which they were desperate to avoid. For a generation of bankers used to kicking the can down the road, the day of reckoning had arrived.

Banking industry’s stressed loans were at 12.3% of total assets in December 2016, up from 9.8% in March 2014.

All the 12 accounts in the first batch referred to bankruptcy courts are those which already had their loans restructured with repayment tenors extended and lower interest rate. These were under the so-called Corporate Debt Restructuring (CDR), the most favoured solution for both bankers and borrowers.

Now that bankruptcy is a reality, bankers are preparing for a paradigm shift in the way banks operate. “We are on the path to setting up sounder systems,” says Sunil Srivastava, deputy managing director at State Bank of India.

“Though the transition will be painful, the tracks which have been laid will make it smooth for sellers as well as borrowers. It had to happen sometime, so it is better to make use of the opportunity that the crisis has given us.”

SOCIALIST BANKING

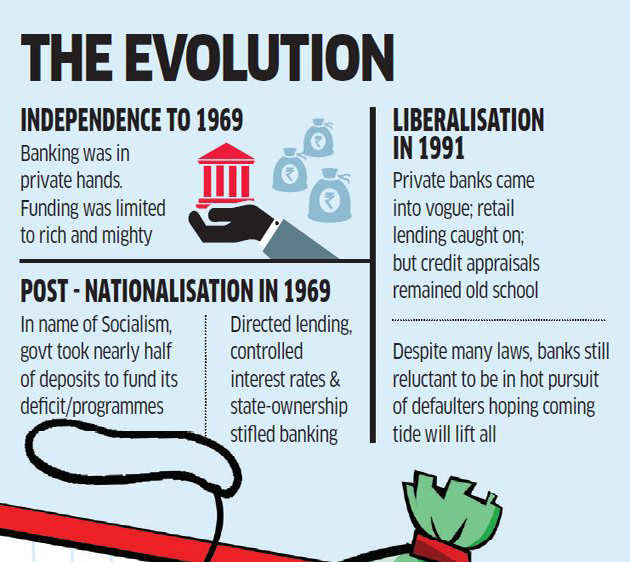

Since liberalisation, the banking industry has transformed in many aspects – with new private lenders, giving out retail loans, adapting technology, credit scores for borrowers, rating companies and many more.

But the way banks lent to corporates did not change much and they were on a wing and a prayer for the recovery rather than cutting losses and taking legal recourse, which was ineffective due to the snail-paced judiciary.

With the regulator blessing the not so good practices like the CDR mechanism that suited everyone, banks managed to paper over the cracks in their institutions for years.

“Earlier, most of the banks did not want to recognise loan defaults and they just kicked the can down the road,” says KVS Manian, president – corporate, institutional and investment banking at Kotak Mahindra Bank. “They were not ready to face the reality.”

Most banks lived on the lessons of past. When bad loans swept the industry in the ’90s, banks gave promoters concessions and many were lifted when the tide turned. They were hoping for that to repeat. But the magnitude of the problem this time was enormous and the regulator now was wearing a global hat!

The Booth School of Business’ Finance Professor Dr. Raghuram Rajan as the regulator was set to pull the industry from its archaic practices and end the ‘divine right’ of unscrupulous promoters. When the RBI ordered its Asset Quality Review in 2015, bankers were fuming.

WHAT THE DOCTOR ORDERED

Indian banks were unique. When the global best practice to revive a company struggling with poor cash flows is to cut debt and bring in equity, Indian banks did the opposite. They threw good money after bad.

Banks sanctioned more loans to struggling firms with which the failing firm would pay up to avoid default. Borrowers also got their repayment terms extended at lower rates.

This practice just worsened the problem. If a company did not have enough cash flows to service Rs 100-crore loan, how could it repay Rs 130-crore loan? But that’s how the CDR operated in most cases.

That the 12 of the big cases referred to the bankruptcy courts after RBI direction were all restructured loans in the past indicate that assumption on cash flows were optimistic.

With the gap to revive an asset set at just 12 months after becoming a bad loan, many promoters would voluntarily rush to the bankruptcy courts to retain their assets rather than wait for banks to initiate action.

“The ordinance will fast-pace initiation of insolvency proceedings by a corporate debtor as promoters are likely to rush for filing insolvency on their own the moment a loan turns bad and prior to expiry of the one-year cap,” says Babu Sivaprakasam, partner at Economics Laws Practice.

CASH VERSUS ASSET

Bankers were no exception to herd mentality. The industry did not evolve underwriting standards required to funding the enormous projects it did in the decade between 2002 and 2012. But they followed one another, especially in consortium lending.

Most of the banks’ books look alike barring exceptions such as HDFC Bank and IndusInd Bank, which consciously avoided infrastructure projects.

State-run banks along with ICICI Bank and Axis Bank have identical problems.

“Banks should have independent in-house expertise for evaluating these projects,” says TT Ram Mohan, professor at the Indian Institute of Management, Ahmedabad. “They should not just go with the lead banker in the consortium which is what typically banks have done.

What is an acceptable risk on SBI’s book is not an acceptable risk on Dena Bank’s book. You can’t say that just because the lead bank will monitor, I will go off to sleep.’’

Historically, Indian banks focused on value of assets of the borrower rather the cash generated by those assets, which is a better scale to assess credit risk.

This led to inflating of asset values and a false sense of hope that in the event of default, they would be able to recover, though they knew well that it was next to impossible to do so quickly when the courts were not up to it.

Future assessments of credit would be determined by cash flows of a company rather than what it owns. And banks could be eager to restructure loan covenants much before the default happens since it is fairly clear that there is no other way for banks to sweep defaults under the carpet anymore.

“We have to develop a culture where even when an account is standard, banks should be able to give them discount and help the borrower when he gets into trouble,” says former regulator Chakrabarty. “Our problem is that banks don’t give any concession to the customer, but do so only after it is classified as NPA.”

That’s what is probably set to change – for lenders and borrowers – permanently.