Bond investors who have lent blue-chip companies $181 billion this year to fund acquisitions just got a tough reminder that mergers can fail.

Money managers holding $35 billion of Anheuser-Busch InBev NV bonds lost $137 million in one day recently when it looked like the brewer’s planned purchase of rival SABMiller Plc might fall apart. A busted deal would have allowed AB InBev to buy back the bonds it issued to fund the acquisition at 101 cents on the dollar, a bargain price for debt trading as high as 106.6 cents.

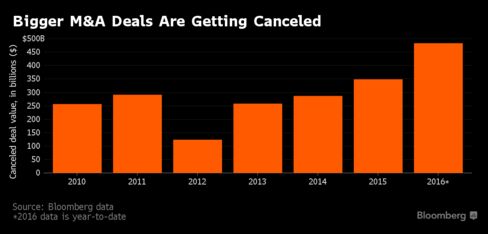

In the end, AB InBev and SABMiller patched up their differences, and for most fund managers the paper losses were just a blip. But more than $486 billion of mergers and acquisitions have failed this year, an amount exceeding what was canceled in all of 2015, and if additional deals fail, investors’ losses could be outsized. Aetna Inc.’s $35 billion bid to buy Humana Inc., for example, which is being contested by the U.S. Justice Department, could cost investors in some Aetna bonds more than $300 million if the deal collapses. Walgreens Boots Alliance Inc., which is trying to buy Rite Aid Corp. in a deal antitrust authorities are investigating in depth, could cost money managers more than $39 million.

Potential losses are big because bond prices have risen so much this year. Yield-starved investors have clamored to buy debt in recent months after the Federal Reserve slowed its plans to raise rates. When a deal goes bust, the acquirer can often buy back the debt it issued to fund the acquisition at 101 cents on the dollar, a process known as calling the debt. That level is far below where many of the bonds are now trading.

Money managers may not be paying enough attention to the risk of takeover deals failing, said Dan Heckman, a fixed-income strategist at U.S. Bank Wealth Management, which oversees $133 billion. “People are just willing to bid these bonds up beyond what may be a fair value based upon that call feature,” he said. “There’s a desperate search for income.”

Merger deals are at risk as U.S. regulators clamp down on possible antitrust problems, and after the U.K. voted to leave the European Union, Goldman Sachs Group Inc. analysts wrote in June. Merger-linked debt accounts for around 20 percent of this year’s issuance, according to data compiled by Bloomberg.

Antitrust concerns are particularly high now, said Ira Gorsky, an equity analyst focused on event-driven trades including mergers at trading and research firm Elevation. U.S. President Barack Obama issued an executive order in April to press government agencies to refer evidence of anti-competitive behavior to the Justice Department and the Federal Trade Commission. The Democratic party platform for the upcoming presidential election mentions stronger antitrust enforcement as a goal, the first time that idea appeared in a platform since 1988.

“Some of these deals have really pushed it,” Elevation’s Gorsky said, referring to large acquisitions that have been announced but have not yet closed.

‘Watching Closely’

With more deals potentially falling apart, some investors are focused more on a bond’s absolute price in dollar terms, said Jason Shoup, a portfolio manager and fixed-income strategist at Legal & General Investment Management America. Investment-grade investors usually focus on the yield a security offers relative to Treasuries, a measure of risk known as a spread, rather than its price.

“Break-up risk is one thing we’re kind of watching quite closely right now,” Shoup said. Legal & General Investment Management America manages $134 billion.

The last company to call back debt after a failed deal was Halliburton Co., which redeemed $2.5 billion of five-year and seven-year notes it issued in November to fund its failed takeover of Baker Hughes Inc. That debt traded as high as 103.2 cents on the dollar before falling to just below 101 cents after the deal was terminated.

Most investors in these deals bought the bonds when they were issued around par, so any losses from selling at 101 would mostly be on paper after the bonds have rallied in recent months. But with yields having fallen so much, investors should consider the risks, Shoup said.

“It’s an unfortunate consequence of the rate rally,” he said.