Mergers between utility companies are about as dry as corporate dealmaking gets. But that’s not why traders hate them.

For those in the arbitrage game, who stake their returns on when and at what price transactions close, deals involving electric or gas utilities often take too long and carry too much risk. It’s a heavily regulated industry, so the obstacles go beyond the usual high-level antitrust probes. States, municipalities and utility authorities — whose actions are even tougher for an outsider to predict — can try to pull the plug on these mergers, too.

The latest near-debacle was Chicago-based Exelon’s $12.2 billion acquisition of Washington-based Pepco. The companies faced heavy pushback from the District of Columbia Public Service Commission, Washington’s mayor and other city officials. Their transaction ultimately cleared after certain concessions were made, but it took nearly two years to get there.

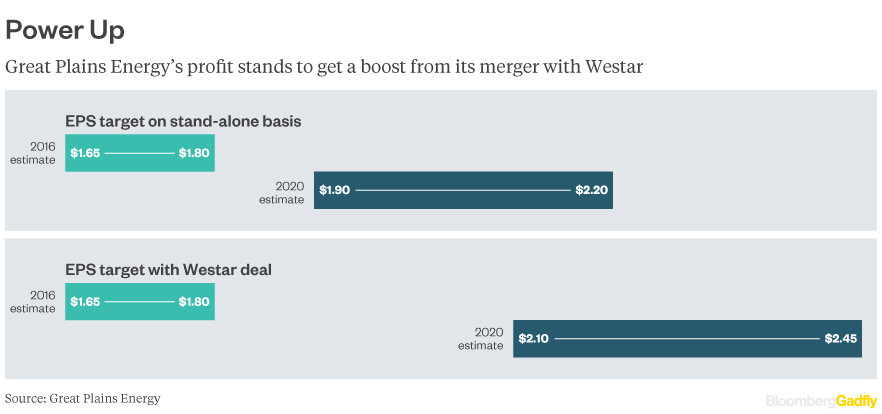

Now, it seems some investors are giving a cold shoulder to Great Plains Energy’s $12.2 billion takeover of Westar Energy, which will bring together two power providers operating in Kansas and Missouri. The fear is that they could wind up like Exelon and Pepco. But Great Plains and Westar may be in a better position.

The two companies are a natural strategic fit. Rather than pursuing a target in a different part of the country, Great Plains is essentially buying its neighbor (its headquarters is only about an hour away from Westar’s). While the majority of Great Plains’ customers hail from Missouri, on the conference call following the deal announcement, Chairman and CEO Terry Bassham noted that it’s also been operating in Kansas for more than 100 years and has “developed strong relationships with stakeholders throughout the state.” Great Plains and Westar also already share ownership of a nuclear station and two power plants in Kansas. Their geographic proximity enhances the cost-cutting opportunities, which the companies estimate to reach $200 million annually starting in year 3. They say the deal will also mitigate rate increases for customers over time.

That’s not to say this is a done deal. Bassham himself cautioned that there’s a lot of work to do to close the transaction, which he expects to occur in the spring of 2017. The deal requires a nod from the Kansas Corporation Commission, but the companies expected they wouldn’t need approval from the Missouri side. On Wednesday, however, the Missouri Public Service Commission said it will consider arguments made by its staff that Missouri has jurisdiction over the deal. It’s concerned that the increased cost of capital could lead to higher rates for Missourians.

As I wrote last week, this is certainly a debt-laden deal, so you can see where that concern is coming from. However, Great Plains assured analysts that it’s comfortable with this amount of leverage and is committed to maintaining its investment-grade rating. S&P reaffirmed its BBB+ rating for Great Plains, but changed its outlook to negative from stable.

Even with the debt involved, the merger seems more straightforward and sure than Exelon-Pepco and some of the other deals attempted in the industry. If that’s the case, the Westar takeover spread may present an opportunity. On Wednesday, Westar shares traded about 7 percent below the value of Great Plains’ cash-and-stock offer. The average spread for open takeovers larger than $1 billion in the U.S. was about 3 percent as of Wednesday afternoon, according to data compiled by Bloomberg. Of course, the timing on this one means it’s not a huge annualized return, but it’s worth pointing out.

Great Plains’ M&A track record is good so far. In 2008, it completed a $2.7 billion acquisition (including net debt) ofAquila, another utility owner in Kansas City, after securing all the necessary approvals. The company said the synergies from that deal exceeded initial expectations.

It’s a good bet that Great Plains can power this one across the finish line, too.

–With assistance from Elaine He.

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Tara Lachapelle in New York at [email protected]

To contact the editor responsible for this story:

Beth Williams at [email protected]